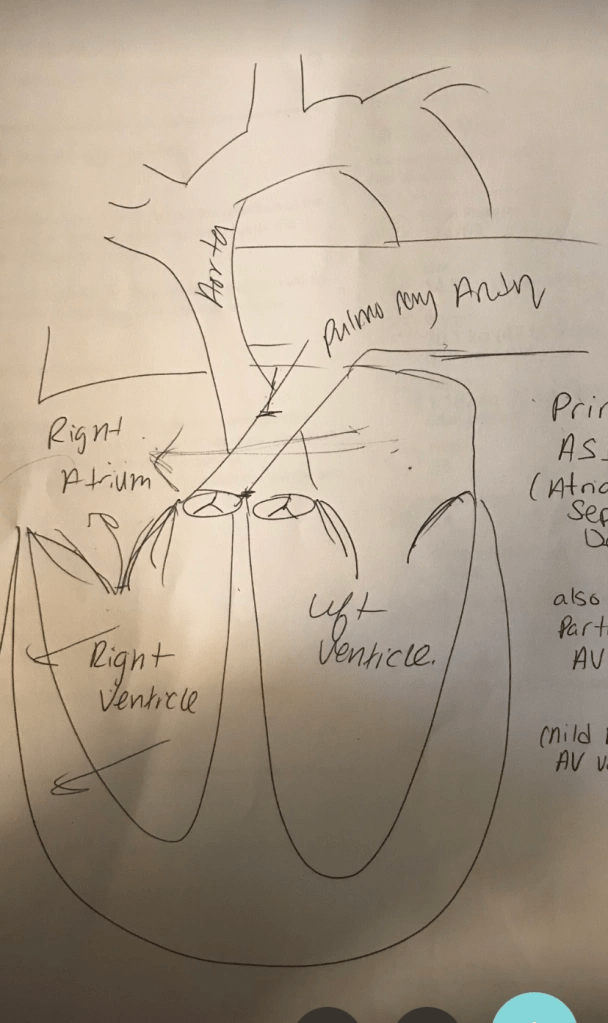

Two years ago today, I sat in a small windowless room at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia as a pediatric cardiologist, a stranger, sat down and began drawing a picture of a heart. It was my daughter’s heart. It was imperfect. It was broken. I listened as she explained that at some point at the beginning of my pregnancy, my daughter’s heart never finished forming the way it was supposed to. She told me about the surgery needed to fix her little broken heart. She gave me statistics and survival rates and asked if any children in my family had suddenly and unexpectedly died. She probably talked for five minutes, but it felt like an hour. I sat there with my thighs stuck to the plastic seat, trying to take it all in. I tried to pay attention but only heard half of her words. Grace sat beside me the whole time. So there I sat, trying not to cry or scare her. Finally, the doctor explained the logistics of the surgery. She told me that the surgeon would have to saw through her sternum to get to her heart. Then, she said they would have to stop her heart to perform her surgery. This was my breaking point. Fat tears started running down my cheeks and filling up my mask.

Grace, who had been playing a computer game while we talked, looked up at me and said, “Mommy, am I going to die?” At that point, I didn’t even know how to begin to answer her. I didn’t know what questions to ask, and I didn’t know how to explain this in a way that she would understand. A week before, we celebrated her 7th birthday. She was healthy then. She was whole. Her heart was fine. Now, she was weeks away from surgery and recovery that most adults don’t have to endure. A summer already altered because of a global pandemic would now be filled with medical tests, surgeons, doctors, and lots of time in bed, inside, away from friends.

Somehow, despite ER visits that included chest x-rays, three bouts of pneumonia, and dozens of visits to the doctor, no one had ever noticed her murmuring heartbeat. Somehow, despite all of the extra ultrasounds due to my “geriatric pregnancy,” no one noticed the large hole in her heart. Somehow, her body, though struggling, had continued to survive. Three weeks after the appointment with the cardiologist, I was sitting in the hospital hallway waiting for the call to tell me that her heart was beating again. Then they called to tell me her sternum was pinned back together. Then, we began the healing process.

I went through all of the motions of this like a numb machine. Worst-case scenarios swirled through my brain on a daily basis, even when she was “in the clear.” Eight or nine months after her surgery, I found myself sitting on the edge of the bed sobbing, seemingly out of nowhere. I tend to stay on the positive side of things and focus on all the good, but in reality, even though people constantly remind me that she is ok, I have spent the last two years fearing something else will go terribly wrong. The trauma of that day is still with me, and I am allowing myself to feel that trauma and sit with it.

Someone once said that having a child is like having your heart walk around outside your body. When you are told that heart may cease to exist, and she has become your whole world, it feels like a vice squeezing your chest and stealing your breath. Unfortunately, that feeling remains long after the threat is gone and your child is well again. I have learned from fellow heart moms that this is common. We worry about every rash, splinter, or blue lips when our child comes in from the cold. The slightest fever in our child can send us back to that small windowless hospital room where we learned how fragile life truly is. So, be patient with us and know that two or five years still may not be enough time for us to feel okay about what happened. Like grief, trauma is an unpredictable beast with its own timeline.

“After all, when a stone is dropped into a pond, the water continues quivering even after the stone has sunk to the bottom.”

~Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha

In the end though, we pumped up the music, moved the tables out of the way, and danced it out. No matter what happened between us, we were always able to end an evening with dancing and laughter: pure joy. There was nothing a little Aretha Franklin couldn’t fix.

In the end though, we pumped up the music, moved the tables out of the way, and danced it out. No matter what happened between us, we were always able to end an evening with dancing and laughter: pure joy. There was nothing a little Aretha Franklin couldn’t fix. shovel, looked up at the sky, and opened her mouth. A snowflake landed on her tongue and she closed her eyes, smiled, and savored it like it was the most delicious thing she had ever tasted. I stopped shoveling. I looked at my beautiful daughter running down our beautiful snow covered street. All I could hear was her laughter. I looked up to the sky and opened my mouth to catch a snowflake. A big fat wet snowflake hit my tongue and another went right in my eye, temporarily blinding me. I let out a teenage giggle and stood there, in the moment, and took in the taste, sound, and chilly air.

shovel, looked up at the sky, and opened her mouth. A snowflake landed on her tongue and she closed her eyes, smiled, and savored it like it was the most delicious thing she had ever tasted. I stopped shoveling. I looked at my beautiful daughter running down our beautiful snow covered street. All I could hear was her laughter. I looked up to the sky and opened my mouth to catch a snowflake. A big fat wet snowflake hit my tongue and another went right in my eye, temporarily blinding me. I let out a teenage giggle and stood there, in the moment, and took in the taste, sound, and chilly air.

I still want to see him lift up my daughter and swing her around the room or even just read her a book. I still have moments of shock, denial, and bargaining. I still see sweet old men with their socks half way up their legs on a hot day and burst into tears. The stages of grief keep looping around. There is nothing final or linear about them.

I still want to see him lift up my daughter and swing her around the room or even just read her a book. I still have moments of shock, denial, and bargaining. I still see sweet old men with their socks half way up their legs on a hot day and burst into tears. The stages of grief keep looping around. There is nothing final or linear about them. too expensive and you only kind of like them, but they remind you of your dad’s fig tree. Grief is watching your daughter blow out birthday candles for the fourth time and still wishing your dad was one of the people standing there singing to her. Grief is finding it hard to go to church because you can’t go there without thinking of your dad and all those Sunday mornings of him standing in the pulpit. Grief is wishing you had asked more questions or taken more videos or spent more time listening back when you had time. Grief is wishing you had said “I love you” just 10 more times.

too expensive and you only kind of like them, but they remind you of your dad’s fig tree. Grief is watching your daughter blow out birthday candles for the fourth time and still wishing your dad was one of the people standing there singing to her. Grief is finding it hard to go to church because you can’t go there without thinking of your dad and all those Sunday mornings of him standing in the pulpit. Grief is wishing you had asked more questions or taken more videos or spent more time listening back when you had time. Grief is wishing you had said “I love you” just 10 more times.

As a parent, I don’t want my daughter to ever feel this shame. As weird as she is, or unconventional, or totally “normal,” I want her to just love herself and be proud of the amazing little being that she is. This desire for her makes me more aware of the fact that I need to “get over it, show up for my life, and not be ashamed.” I truly believe when any of us can be ourselves, embrace our quirks and differences, and celebrate those things that make each one of us unique, we will be able to free ourselves of shame and genuinely live our lives.

As a parent, I don’t want my daughter to ever feel this shame. As weird as she is, or unconventional, or totally “normal,” I want her to just love herself and be proud of the amazing little being that she is. This desire for her makes me more aware of the fact that I need to “get over it, show up for my life, and not be ashamed.” I truly believe when any of us can be ourselves, embrace our quirks and differences, and celebrate those things that make each one of us unique, we will be able to free ourselves of shame and genuinely live our lives.  So, though a nicer car or a bigger house would be great, I have to say that I think “the good life” is really all those little moments with the ones we love that fill up everyday and cost us nothing. It’s a roof over our heads and having enough. It’s having a job that makes us happy. It’s little fingers and little toes and big toddler smiles and belly laughs. It

So, though a nicer car or a bigger house would be great, I have to say that I think “the good life” is really all those little moments with the ones we love that fill up everyday and cost us nothing. It’s a roof over our heads and having enough. It’s having a job that makes us happy. It’s little fingers and little toes and big toddler smiles and belly laughs. It